root@jsnl.io

:

~/essays

$

render hierarchies.md# The obedience factor - June 20, 2025

The obedience factor

The "obedience factor" of a hierarchy represents the degree to which subordinates in the hierarchy follow orders given by superiors. The obedience factor of any hierarchy is implicitly determined by a variety of environmental factors, most of which are controlled by the leaders of the hierarchy. The obedience factor of a subhierarchy is heavily influenced but not entirely determined by that of its super hierarchy. The obedience factor plays an important role in defining the overall function of the hierarchy, specifically by modulating the risk that the hierarchy or any of its components behave unethically, and increasing or lowering collective accountability within the hierarchy. Leaders of any hierarchy should think carefully about the obedience factor of their organization and align it with their strategy and risk tolerance.

Modeling obedience

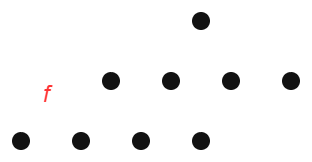

The obedience factor can be loosely modeled as a parameter of hierarchies,

f, representing the probability that a subordinate obeys an order from their

superior. In a hierarchy with an obedience factor of 1.0, every order is

followed exactly, constituting an authoritarian hierarchy. Conversely, in a

hierarchy with an obedience factor of 0, no orders are followed, and the

hierarchy degenerates, effectively ceasing to be a hierarchy at all. [1]

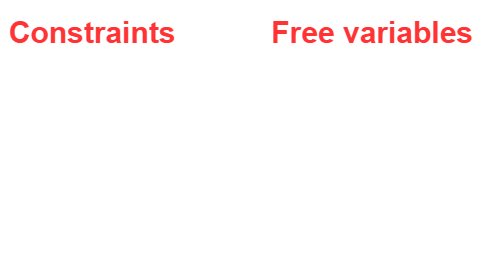

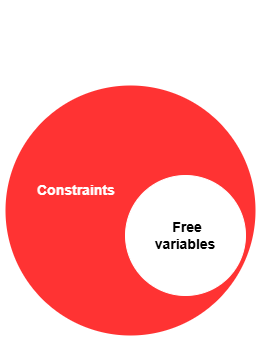

In any hierarchy, an order is a set of instructions given to a subordinate to behave in some particular way. The set of all possible behaviors available to a hierarchy is called the "solution space" (in this sense, a subordinate's job is to select a behavior from the solution space which satisfies the order). An order is comprised of two parts:

Constraints are the core requirements of the order. Constraints can be explicit in the order, but are arguably more often implicit and supposed to be inferred by the subordinate. Constraints are so called because they constrain the subordinate to a subset of the overall solution space. In the order, "finish the report by the end of the week", there are the following constraints:

- The report must be finished (i.e. complete, likely relative to a previously- or implicitly-defined quality expectation).

- It must be so by the end of the week (where the end of the week probably refers to the end of day on Friday; not Sunday).

Free variables are the parameters related to fulfilling the order that are left to the subordinate's discretion. Free variables represent the subset of the solution space within which the subordinate must operate. From the order above, the subordinate likely has agency over:

- When to block time to work on the report.

- The contents of the report.

Irrespective of whether a hierarchy falls more closely to the degenerate or

authoritarian end of the spectrum, orders offer subordinates varying degrees of

freedom and agency. As orders propagate down the hierarchy, free variables are

systematically constrained by superiors exercising their discretion until

eventually the lowest-level subordinates have the smallest free variable domain,

at least relative to the original top-level order. [2] In other words, as a

top-level order is digested into many lower-level orders deeper in the

hierarchy, the constrained domain monotononically increases and the free

variable domain monotonically decreases. This property is guaranteed in

hierarchies where subordinates cannot exercise discretion to remove

constraints provided by their superior (i.e. f = 1.0) in orders to their own

subordinates (which would be a form of disobedience). In hierarchies with

obedience factors less than 1.0, the free variable domain can increase as an

order moves downward, but on average we still expect it to shrink (i.e. on

average, we expect lower-level members of the hierarchy to have less agency

within the global solution space than higher-level members).

When hierarchies misbehave

All hierarchies misbehave. A hierarchy is misbehaving when it or some subhierarchy within it (including a subhierarchy of one individual) engages in activity that is counterproductive to the hierarchy's objectives, illegal, or unethical. Of course, much of whether something is counterproductive, illegal, or unethical is subjective. With that in mind, instead of discussing specific examples of hierarchical misbehavior, we can discuss the properties of misbehavior generally and the exercise of applying them to specific instances is left to the reader. There are two reasons why we know all hierarchies misbehave. First, because humans are imperfect judges of strategy, tactics, legality, and ethics (partly because they're subjective, but also because people make mistakes even when the material is objective). And second, because individual incentives never perfectly align with the hierarchy's interests.

When misbehavior happens, it's because one or more individuals within a hierarchy select a "bad" solution (i.e. bad behavior) from the solution space. For any specific individual, solutions are selected from either the constrained set or the free variable set as defined for them by their superior(s). When an individual misbehaves by selecting a behavior from the constrained set, they are disobeying their superior. When misbehavior is selected from the free variable set, the subordinate is obeying their superior. In some of the latter cases, a subordinate's free variable space will only contain bad behaviors. In these cases, their superior constrained their free variable space to include only counterproductive, illegal, or unethical solutions, effectively ordering them to misbehave.

Large-scale misbehavior

In hierarchies with very high obedience factors, the risk of large-scale hierarchical misbehavior is higher than in hierarchies with lower obedience factors.

Consider an obedience factor f equal to 1.0. If a member high in the hierarchy

constrains one of their subordinates (a leader of a large subhierarchy) to a

free variable space consisting exclusively of bad behavior (i.e. again, orders

them to misbehave), then the probability that all members of the subhierarchy

will engage in bad behavior is 100%. Specifically, for any "leaf" member (i.e.

lowest level member of the hierarchy with no subordinates), the chain of orders

up to the original bad-acting leader all offer free variable spaces with only

bad behaviors. Since f is 1.0, no subordinate leader can remove their

superior's constraints to include good behaviors in their subordinate's free

variable space or reject their superior's order entirely (both of which would be

disobedience). Thus each leaf member, who is only subject to the f of 1.0,

will obey the order and engage in misbehavior.

This example demonstrates that high obedience factors are dangerous for a hierarchy. A single bad-acting leader can order an entire suborganization to misbehave and because the obedience factor is so high, their subordinates are unlikely to act as fail-safes and override their order. Moreover, because leaders are likely aware of the hierarchy's obedience factor (in a loose sense), the knowledge of a high obedience factor de-risks the act of ordering their subhierarchy to misbehave since the likelihood that they'll be challenged is reduced.

A savvy leader of a subhierarchy might try to exploit these properties by

increasing the obedience factor of his subhierarchy to be higher than that of

the larger hierarchy. The result would be a subhierarchy calcified to serve its

leader's demands, evil or not, potentially at the expense of the larger

hierarchy. Because the incentives of the subhierarchy leader can never be

perfectly aligned with that of the larger hierarchy, subhierarchy leaders that

manage to implement this "Roman General Effect" can focus exclusively on their

own interests which might include seizing control of the larger hierarchy. The

notion of the obedience factor as the probability of an order being obeyed

between any superior and their direct subordinate is insufficient to

accurately model this particular tactic because a subhierarchy with f equal to

1.0 confers all the same mischievous advantages to the subhierarchy leader's

subordinates as it does to himself. It's true that the subhierarchy leader has

hardened his organization to serve his interests, but he has also done so for

all of his subordinate leaders and their suborganizations. The Roman General

Effect is actually achieved when an entire subhierarchyis manipulated to have a

very high degree of obedience to its top-level leader that is strictly higher

than that to its lower-level leaders.

Top-level hierarchy leaders should be wary of the effects of too high obedience factors, including the ethical implications, increased risk of large strategic and tactical blunders, and potential for subordinate leaders to usurp power. The obedience factor should be high enough for the organization to operate effectively, but not higher.

Chaotic misbehavior

If high obedience factors, increase the risk of large-scale misbehavior, what

happens when the obedience factor is too low? In the case of a hierarchy with an

obedience factor f of 0, the hierarchy degenerates. Since subordinates never

obey orders, misbehavior is indeed pervasive, but only ever happens on the

smallest possible scale: the individual. Coordinated misbehavior is impossible;

chaotic misbehavior is everywhere. (This discussion reveals the fundamental

limitations of the f model of the obedience factor since it assumes obedience

is necessary to control hierarchies and generally oversimplifies how the

behavior of hierarchies is determined. Nonetheless, it's a valuable exercise.

See comment [1] for more nuance.)

Unfortunately for our zero-obedience organization, this chaotic misbehavior renders it completely ineffective at achieving its broader objectives. I assume this is palatable to very few leaders.

Still, I don't discard the concept. Anarchy (of which I believe a zero-obedience organization is an instance of) is a legitimate subject of thorough discussion that I haven't studied. And in this example, it's clear that a zero-obedience organization has certain properties that are desirable. Its tendency toward chaotic misbehavior makes coordinated misbehavior much more difficult. The largest atrocities in history weren't committed by low-obedience organizations. If you accept that coordinated people can achieve greater feats than uncoordinated people (the premise for collaboration), then you might also accept that coordinated people can commit greater evils than uncoordinated people.

That might be true, but I'm concerned that it may be easier for uncoordinated people to incidentally combine forces to achieve a negative effect than to do so for a positive effect. [3] If so, while a zero-obedience organization succeeds in reducing the likelihood of both coordinated goodness and coordinated evil, it also accepts an asymmetrical risk of uncoordinated evil relative to uncoordinated good. In that case we'd be better off mitigating the risk of coordinated evil (much more damaging than uncoordinated evil) and maximizing the efficacy of our efforts to create coordinated good. In other words, we should design hierarchies to be fault tolerant against evil or mistaken leaders ordering large organizations to behave badly and be sufficiently ordered to achieve great things. In order to do so, the obedience factor has to be high enough to achieve coordination, but not so high that the organization is exposed to unacceptable risk of committing large-scale, coordinated misbehavior.

Accountability

The obedience factor also impacts how we identify who's accountable when a hierarchy misbehaves. In the introduction to this section, I noted that misbehavior happens when one or more individuals within a hierarchy select a "bad" solution from the global solution space. I also distinguished between two kinds of misbehavior: obedient and disobedient.

Obedient misbehavior is when a subordinate selects a bad solution from the free variable space. They were given a certain degree of agency by their superior and used it to do a bad thing (perhaps deliberately; perhaps not). A variant of obedient misbehavior called forced misbehavior is one in which the subordinate's free variable space is exclusively bad behavior-- they are ordered to misbehave. This is in contrast with instances where a subordinate has access to good behaviors in their free variable space and yet elect to do a bad one anyways.

Disobedient misbehavior is when a subordinate selects a bad solution form the constrained solution space. They choose to behave in a way that was either explicitly or implicitly forbidden by their superior.

In any hierarchy, superiors are always accountable for the misbehavior of their subordinates, but there's a question of degree. When a subdivision of the accounting department commits fraud, the CEO is accountable, but she's not necessarily fired. Was she aware of the fraud? Worse, did she order it? Or was this an instance of disobedient misbehavior by an isolated middle manager followed by several instances of obedient misbehavior by his subordinates? The CEO probably should be held accountable for not establishing error-detecting systems to make fraud more difficult (or for not directing someone to do so), but the degree to which she should be held accountable for the fraud itself is not immediately clear.

It's also worth noting that in the context of the obedience factor model,

accountability is not the same as ethical culpability. In this context,

accountability is simply about attributing responsibility for the end behavior

of a hierarchy. When f is 1.0, subordinates ordered to do bad behaviors will

do so. They are entirely unaccountable for any component of the hierarchy's

behavior since they were afforded literally zero agency. In real life, there is

no such thing as truly having no agency. There are situations where agency is

very close to, or practically, zero, but even in those situations, if a

behavior is bad enough, I know many people will attribute a non-negligible

degree of moral culpability to individuals who are negligibly accountable for

the hierarchy's behavior.

In hierarchies with very high obedience factors, accountability will generally fall on fewer individuals, usually higher in the organization. Large-scale misbehaviors, which are more common in high-obedience hierarchies, can be attributed to a single instance of obedient misbehavior that precipitated many instances of forced misbehavior. Because the obedience factor is high, as soon as one leader elects to order his subordinates to misbehave, they and all of their subordinates are forced to do so as the entirely-bad free variable space propagates downward. Moreover, because disobedient misbehavior is so rare in these organizations, when misbehavior does happen, it is almost certainly because a superior allowed bad behaviors to remain in the free variable space given to subordinates (perhaps due to malintent, incompetence, or trust) rather than because a rogue subordinate removed constraints or elected to pursue a behavior in the constrained space. Of course, in cases where lower-level individuals and leaders use their discretion to do and order bad behaviors available in the free variable space, they are not exempt from accountability.

Unsurprisingly, accountability in low-obedience hierarchies is broadly dispersed between members of the hierarchy. This follows from the fact that members of low-obedience hierarchies have a higher degree of agency and are in a better position to reject orders to behave badly. They hold more responsibility for regulating the behavior of the hierarchy. Still, skilled consensus builders would likely rise to some kind of leadership role rooted in influence rather than granted authority, and those individuals would bear disproportionate responsibility for the successes and failures of the group.

Influencing the obedience factor

I suspect there are a myriad of mechanisms impacting the obedience factor of a hierarchy. Some that come to mind are listed below.

May increase obedience:

- Threat of negative consequences for disobedience

- Trust in leadership

- Desire to elevate or remain in the hierarchy

- An interest in the hierarchy's stated objectives (financial, emotional, or otherwise)

- A sense of being impactful (i.e. belief that one's behavior matters)

- A sense of agency (i.e. orders issued with larger free variable spaces; a sense of agency allows individuals to yield agency)

- A sense of belonging to the group rather than being an individual

May decrease obedience:

- Rewards for disobedience

- Low trust in leadership (e.g. belief that leadership is incompetent)

- Poor alignment between individual and organizational incentives

- Existence of whistleblower infrastructure (i.e. the capability to report superiors to an internal policing arm)

- Low levels of individual autonomy (i.e. orders often issued with very small free variable spaces; a lack of agency incentivizes individuals to claim it)

Comments

[1] The notion of hierarchy degeneracy is borrowed from the theory of

binary search trees which

observes that a binary search tree (with average case O(log n) search) can

degenerate to a linked list

(O(n) search) if elements are inserted in sorted order. (Inserting fully

sorted elements is sufficient but not necessary for a BST to degenerate to a

linked list. Inserting even partially sorted elements can cause a BST's search

operations to decay to O(n).) If no one in a hierarchy ever obeys their

superiors, then the it's a hierarchy in name only. The organization degenerates

to one steered by its most skilled power consolidators and not (necessarily) its

named leaders.

One could argue that an obedience factor of 0 is either strictly impossible or does not in fact cause a hierarchy to completely degenerate since a superior could leverage the knowledge that all of their orders will be disobeyed to shape the behavior of their subordinates nonetheless. Suppose a subordinate is given the order, "do not delete any of the documents". If the obedience factor is 0, the subordinate must disobey the order because there's a 0% chance that they obey it. In other words, there's a 0% chance they do not delete any of the documents, so they must delete at least one document.

Clearly, this is not what we mean when we say disobedience. In this scenario, a disobedient subordinate might delete some or all of the documents, but they also might not. Their superior's instruction is immaterial in determining their actions. Whether they incidentally do what their superior instructed is irrelevant. The obedience factor might be better defined as the degree to which an individual's behavior is governed by their superior's orders, so the probabilistic model of the obedience factor presented above is fundamentally limited.

In any case, this suggests that a lack of obedience does not necessarily imply a lack of control. Control and obedience are linked, but are not the same. Some organizations probably very successfully control members of their hierarchy despite low obedience. I suspect that the predictability of an organization's members is the most important factor in establishing control in a hierarchy. Obedience creates predictability, but predictability is not only created by obedience. A poker player that never bluffs is definitely not obedient to their opponents, but they are very predictable which makes them easy to control.

In a true zero-obedience organization, the organization's behavior would be determined by consensus building. In the absence of consensus, the group behaves more or less randomly with each individual serving their own interests. The best consensus builders would probably emerge as group leaders, but not authority figures.

[2] It's true that the lowest-level members of any hierarchy operate within

the smallest solution spaces. But, counterintuitively, small spaces can still

offer an infinite number of options. Consider the one-dimensional space on the

real number line: [0, 1]. It's undeniable that [0, 1] is a strictly smaller

space than [0, 10], [0, 100], and so on. Nonetheless, there are an

infinite number of real numbers in [0, 1]*.

Whether a hierarchy's solution space is truly infinite (i.e. there is an infinite number of behaviors that a hierarchy could engage in) is not clear to me. It depends on how you define "behavior", and I think in any case that discussion would quickly become esoteric (this all might be esoteric already).

Nonetheless, the important point is that very small solution spaces can be still be vast. Even (maybe especially) the brightest people can find challenge, joy, and beauty in incredibly constrained solutions spaces. Chess comes to mind. In terms of the global solution space (all possible behaviors), the order "play chess" is a very constraining one. But with 64 squares, 32 pieces, two players, and a simple set of rules, there are more playable games of chess than atoms in the known universe. Not infinite, but practically!

This is why bright individuals not only can thrive in small domains, but are essential in these spaces. Equally bright people operating in larger domains will necessarily never understand the smaller domains as well as their respective experts. To do so would mean sacrificing expertise in other areas of the larger domain. And yet there is tremendous value in having someone dedicate their entire focus to the small domain: "God is in the details".

Hierarchies can be misunderstood to falsely conflate altitude with talent and value. Capitalist hierarchies, where compensation dramatically increases with altitude in the hierarchy, are a clear example. I accept that altitude, talent, and value are probably positively correlated since steering increasingly large hierarchies to tackle specific kinds of problem spaces is a remarkably small domain in and of itself, but they are not strictly the same.

*Proof: Assume there is a finite number N of real numbers in [0, 1]. N

is clearly at least two since 0 and 1 are both in [0, 1]. Then at random, we

select two adjacent numbers from the N that exist in [0, 1]. The smaller

of these numbers is called r1 and the larger r2. Note that because r1 and

r2 are real numbers, then (r1 + r2) / 2, called r3, is also a real number.

Because r3 = (r1 + r2) / 2 is the average of r1 and r2, we know that

r1 < r3 < r2. Therefore, r3 is in the interval [0, 1] since r1 and r2

are in [0, 1] and r3 is between r1 and r2. Thus, there are in fact

N + 1 real numbers in [0, 1] (and, a corollary, that r1 and r2 are not

in fact adjacent at all). However this contradicts our initial assumption that

there are only N real numbers in [0, 1] (and the fact that r1 and r2 are

adjacent). Therefore, our initial assumption is false so there must be an

infinite number of real numbers in [0, 1].

[3] See the tragedy of the commons as an abstract concept, although I'm not married to its literal accuracy.

root@jsnl.io

:

~/essays

$